This is a translation into Swedish of this article.

Continue reading

How shunning should be used

This is a literature study, where we seek a balanced view of shunning and ecclesiastic discipline as it is presented within the protestant canon of the holy scriptures. We discover that shunning decided by a congregation’s leaders, and disfellowshipping (excommunication) should never be combined as means to protect the spiritual integrity of the congregation. Shunning should be applied towards insincere members, but towards former members only at the sole discretion of the person who performs the shunning.

Waw-consecutive & The Original Language of the Gospel of Mark

Just a little introduction. We have testimony from early Christians, Papias as cited by Eusebios and Hieronymus/Jerome saying Matthew wrote in his own language in Hebrew characters. The remaining books of the New Testament have been assumed by many to have been written in Greek, but some suggest Aramaic, and in the case of the Gospel according to Mark, Latin has been mentioned.

The arguments for Latin are pretty good but not waterproof. This site is a good summary:

http://www.mycrandall.ca/courses/ntintro/mark.htm

Against the idea that it was written in Latin, stands the fact that the Gospel according to Mark is shock full of sentences on the form: conjunction – verb – the rest. This word order is typical of semitic texts. If, in addition, the conjunction seems out of place and is part of a narrative, it is almost certainly a case of waw-consecutive, a semitic phenomenon.

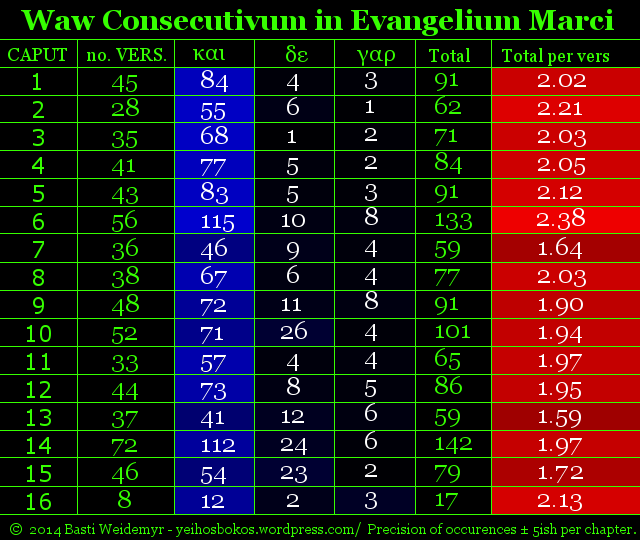

Out of curiosity, I made a little graphic to find out if:

1. this happened where Yesus was speaking, for Yesus probably spoke the mostly semitic language of Syriac/Aramaic.

2. it happened only in sections of the gospel while other parts looked rather Indo-European. For some of the material in Mark may have come from notes made by a disciple and which was common to the authors of Matthew, Mark and Luke. And some of the material probably came from Simon Petros, who worked closely with a certain Mark.

No 1 is not answered by the graphic but it seems that Yesus used waw-consecutive-style constructions a little less than the narrative surrounding the quotes from his teaching. In any case, the waw-consecutives in Mark cannot be explained away as being caused by the Aramaic of Yesus Christ.

No 2 is indicated by the graphic. If there is a breaking point, such that Peter wrote most of some chapters and Mark wrote most of some others, it should be late in chapter 6. However, there are alternative explanations, mainly that from chapter 7 onwards, the focus shifts from the lords miracles and parables to describing events among the disciples and clashes with the pharisees, so the word “but” became more useful in the narrative in place of “and”. Later translators may have begun to feel, around chapter 7, that there were so many “and” that they could not endure it any more and had to omit some or replace them with similar narrative words.

The most obvious conclusion is that waw-consecutive is ubiquitous therein.

In the graphic, occurrences of και, δε and γαρ were counted even when they occurred in constructions that could not be waw-consecutive. The colour indicates number of occurrences per verse and errors may come from the fact that verses have different lengths. A digital copy of Wescot & Hort’s critical Alexandrian Greek text was used.

Finally a word of caution. Discussions about “primacy”, that is which language a scripture was first written in, can seem incredibly convincing to a beginner. Do not be too fast to draw conclusions. Just because some expert has proven you wrong about book X being written in language Y, it does not mean you have to believe that expert when he says all of the books were written in language Z, or you would have to change your stance several times per year. For there is really convincing evidence in all directions and there is no reason to think all of the books were written in the same language. Or to think they were written in just one language.

So the waw-consecutives of Mark suggest a Semitic language because in ancient times translations were usually very literal and mechanical. Not like today when we like to translate thoughts rather than words. So, the word-order betrays a Semitic original, but it may have been released in Latin … or Greek … or both.

And bring us not into what…?

Hold your breath because this is doctrine-critical!

You do not often see Swedish mentioned in the context of biblical translation, but in a lesson about the Lord’s Prayer in Gothic[1], by James Marchand, the word fraistubnjai is connected to its Swedish cognate frestelse.

The lesson is actually a way to show how a 17th century Dutch scholar (Fransiscus Junius) would have understood Codex Argenteus, the Silver Bible.

It says: “in fraistubnjai = looks like the dative of some funny noun ?? As Junius, we would recognize the connection with Swedish frestelse ‘temptation‘, for example. We may have even eaten Janssons frestelse, that tempting dish of tempting dishes.”

Everything about this is fine* except the appearance of ‘temptation‘ next to frestelse which would seem to indicate that the two words had the same meaning. In today’s Swedish and Southern dialects frestelse usually means one of two things: temptation or strain/exhaustion. The English word temptation would cleanly translate into Swedish lockelse, while strain and exhaustion may both be translated to påfrestning, which is probably a hint to the old meaning of the verb fresta that frestelse was formed from.

So far the understanding by a native speaker of a Southern Swedish dialect an my thesis is: fraistubnjai meant any one of trial/exhaustion/challenge rather than temptation. Now, a few examples from a lexicon, namely the excellent Wordbook of the Swedish Academy (SAOB).

Under frestelse we find:

1560: Thenne höglofflighe Furstes Konung Götstaffz älende, betryk, farligheeter och ovpräknelighe frestelser och mootstånd.

EN: This very commendable Principal King Götstaff’s misery, depression, dangers and uncountable frestelser and backlashes.

1660: Konglige Cronan hafwer hos sådane höghe en stor frestelsse.

EN: The Royal Crown has among such high [persons] a great frestelse.

1712: Den följande natten hade vi åter en frestelse af Araberne.

EN: The following night we had again a frestelse from the Arabs.

1750: Denna hastiga omväxling i väderleken, från vackert til en fuktig köld, är en farlig frestelse för helsan.

EN: This hasty change of weather, from beautiful to a moist cold, is a dangerous frestelse to the health.

If the old meaning of frestelse was trial/exhaustion, the usage case from 1660 can be explained as a test [of the person’s loyalty and resistance to temptation]. If the old meaning was instead temptation it would take some imagination to come up with an explanation of the other usage cases and how the meanings of trial/exhaustion established themselves for påfrestning and in the last few centuries gave way to temptation as the meaning of frestelse.

When Janssons frestelse is described as a frestelse, the hearer sees the scent wrap itself around the victims’ noses and necks, wrestle them down on the floor and drag them mercilessly to the table, in much the same way as a pirate, equipped with a knife, wrestles down a traveller, cuts him till he bleeds and leaves him powerless by the roadside as the pirate rides away with the traveller’s silver.

How about other languages?

Greek

The corresponding Greek word is πειρασμόν, accusative of πειρασμός. It is used, among other places, in the Septuagint in Exodus 17:7:

καὶ (so) ἐπωνόμασεν (he called) τὸ ὅνομα (the name) τοῦ τόπου (of the place) ἐκείνου (that) πειρασμὸς (מסה) καὶ (and) λοιδόρησις (מריבה) διὰ (for) τὴν λοιδορίαν (the quarrel) τῶν υἱῶν ( of the sons) Ἰσραὴλ (Israel) καὶ (and) διὰ (for) τὸ πειράζειν κύριον (Yehovah) λέγοντας (saying) εἰ ἔστιν (is not) κύριος (Yehovah) ἐν ἡμῖν (with us) ἢ οὔ (or not).

So here, peirasmos corresponds to massah, which could mean melting or be a substantivation of nassah (נסה) meaning trial, providing a link to the Aramaic below. Massah is usually translated as test (NASB, NIV, NW) here in Exodus, but some, like ASV and King James’ versions stick to tempt.

Other places are: Deuteronomy 4:34 and a similar form in Genesis 49:19, where Gad will get either tempted by tempters or pirated by pirates, unless someone has a better idea. And if pirate looks like a cognate of πειρατήριος it may be because it is.

Latin

Hieronymus Vulgate has: “et ne nos inducas in temptationem, sed libera nos à malo.” Bezae-latin reads similarly.

Codex Vercellensis: “et ne nos inducas in temptationem sed libera nos a malo”

Vulgate Clementianum and some early commentators use the spelling tentationem which may be the same word. Lexicons typically lists the meanings trial and attack for both temptatio and tentatio, then as a third, unusual alternative: temptation. And where was it used in this sense according to lexicons? In Matthew 6:13 and other places in the Vulgate.

Aramaic

This prayer made its appearance in connection with the Sermon on the Mount. It was probably spoken in Gallilean Aramaic or some other Aramaic dialect. The word used here in Old Syriac as well as in the Aramaic of the Peshitta is ܢܣܝܘܢܐ (nesyuna).

Payne-Smith lists trial, temptation and mentions a word spelled the same way but vocalized differently, meaning weak, morbid.

CAL reverses the order of temptation, trial and gives sickness as the other meaning.

Conclusion

Some people do not like to have a conclusion pushed down their throat and in any case, knowlege that leads to life should be accessible to a person who serve God and studies his word with zeal, so you have to draw your own conclusions, possibly based on further research. Peirasmos/nesyuna appears in several places in the New Testament. For example, after Jesus was baptized, he went through something in the desert, and if you want to dig deeper you can read James 1:9-15 in Greek. And whatever you do, do not suffer more fraistubnjai than you have to!

*It is not important but the name Janssons Frestelse was probably applied to this dish for the first time in late 19th century, 250 years after Junius made his translation. See Wikipedia.

[1] Dr James Marchand’s Linguistic Lessons, 2003

http://the-orb.net/encyclop/langling/marchlessons/lingintro.html

Edited 26 April: Moved the comma to its right place in the reading of Codex Vercellensis, and changed the direction of a breathing mark in Exodus 17:7.