It has been a while since I wrote an article. This will just be a brief note to show I am alive and was married in April 2024. I had a bit of the same experience as Hades had when he married Persephone. Zeus allowed him to spend only 4 months per year with her, likewise I cannot yet bring my wife to Sweden, because of Sweden’s super-long processing times of migration applications, but I can fly to her once every third or fourth month.

The history of the name Περσεφόνη ‘Persephone’, and its alternative form Περσεφάττα ‘Persephatta’ are unsure, according to Wikipedia (EN) 2025-09-17. Immediately uppon reading it, I got a crazy idea it should perhaps be parsed (pun intended) PeRaS|SeFaTta. That would work if there exists a Semitic word SFT/SPT which makes sense to the story.

Persephone attracted Hades, who kidnapped her and married her in the realm of the dead. Demeter, her mother grieved and denied all plants from spreading and giving fruit, which caused Zeus to intervene and demand that Hades release Persephone. Hades, however, made her eat some seeds of pommegrenade, thus binding her to his household. As a compromise, she would spend four months of every year with Hades, during which time Demeter refused to let plants grow (=winter), and the rest of her time, she would spend with her mother Demeter.

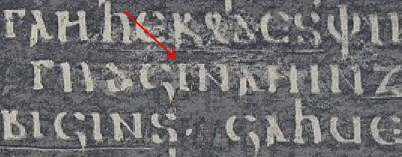

There is a verb for to make somebody eat something which appears in the Babylonian Talmud, tractate Chullin 95b, verse 6 (or 17 in alternative versification). It is also listed in the Comprehensive Aramaic Dictionary (CAL) under a search for samek-phe-taw (which is how I found it). There are also words for lips that might fit better, with the verb פרס peras ‘divide’ as the first part.